Patents are a golden shield not only for the inventors but also for the ever-growing corporate world. However, there is one mistake that many inventors make that could risk their chances of securing a patent. In this article, let’s analyze anticipation laws of patents through the recent decision of the General Courts of the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) in the case of PUMA SE v. European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) and Ors.

The ground rule of any patent is to first secure the priority. Priority can be understood as the first date on which you inform the patent office about your invention. The ideal suggestion is that until then, you should not file an application (either provisional or final) seeking statutory protection for your invention and should keep the invention a secret, with only those associated with the development aware.

The question that arises is what happens if you make your invention public without seeking protection, and what would be the fate of such applications?

To answer this, I would like to introduce readers to the concept of anticipation. In the context of patent law, anticipation refers to the disclosure of the claimed invention, either by the inventor or by another person before the date on which the applicant has sought the protection. The existing patent laws grant some exceptions to the anticipation, and if your case satisfies the essential elements of those anticipations, you can seek protection for your invention.

It is a common understanding that to complete an invention, an inventor has to do trials and tests, and these trials can reveal the invention to the public. Therefore, the drafters of the patent legislation granted a statutory period of 12 months as an exception from anticipation. This means that you can disclose your invention to the public 12 months before applying for patent protection. Is this protection always available? In some jurisdictions, yes. In others, such as India, this has to be coupled with detailed reasoning that during these 12 months, you ran reasonable trials to test the product or the public disclosure was extremely necessary to achieve the finality in the invention.

PUMA v. EUIPO

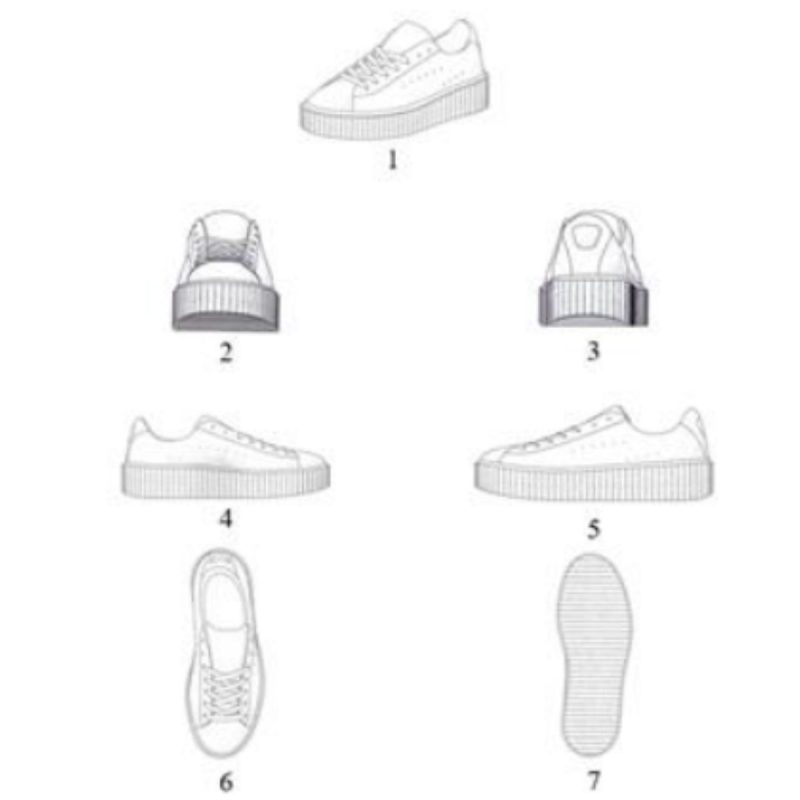

In light of the above discussion, let’s dive into the case of PUMA SE v. the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) and Ors. On 26 July 2016, PUMA made an application before EUIPO for registration of the design of its shoes in Class 02-04, with a priority date of 25 July 2016. See the design below:

On 22 July 2019, an application for intervention was filed by Handelsmaatschappij J Van Hilst BV to invalidate the aforementioned design. The ground taken by the intervener was that the applicant had disclosed the design to the public more than 12 months before the date on which the protection was sought.

It was argued that the well-known singer, businesswoman, and new creative director of PUMA, Rihanna, had already worn the shoes in her Instagram post dated 16 December 2014, therefore invalidating the designs.

On the contrary, PUMA argued that the social media post by Rihanna did not showcase the impugned design clearly, did not reach the European Union’s business circle, and the shoes were not on the market for sale at the time.

Dismissing the arguments put forth by PUMA, the Board of Appeal concluded that Rihanna’s Instagram post did create an overall impression of the product and, therefore, the contested design lacked novelty. Further, the contention that the Instagram post did not reach the European Union’s business circle was stated to be non-maintainable since the said post was reproduced in several fashion newsletters and magazines. Lastly, it was ruled that even if the impugned designs were not available for sale before 25 July 2015, they were published on social media and, therefore, it was enough to show a lack of novelty.

PUMA appealed the above decision before the General Court. The court upheld the decision of the Board of Appeal, finally invalidating the design of the applicant.

This case is a good example of a lack of coordination among the stakeholders and how an eligible intellectual property became ineligible for statutory protection.

Written by Kartik Kumar Aggarwal

Advocate and Patent Agent, Bhartiya Law

You may also like…

Pravin Anand conferred with the APAA Enduring Impact Award

Pre-eminent IP Lawyer and Managing Partner of Anand and Anand, Mr Pravin Anand, has been conferred with the...

The quiet power of confidentiality clubs in SEP litigation

In standard essential patent (SEP) disputes, especially those involving FRAND (Fair, Reasonable, and...

A $10 million patent win reduced to a $1 lesson in damages

In a decision that will resonate as a stark warning to patent litigants, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal...

Contact us to write for out Newsletter